DevOps: Strategies from a Fighter Pilot

Change defines markets, technology, and people. Since the First Industrial Revolution, the pace of change has only quickened. Startups now lead this charge, disrupting industries with innovative business models. These models deliver better customer experiences, greater efficiency, and adaptability. Companies that fail to keep up face an uncertain future. To survive, you must break free from legacy models.

Interestingly, the military thrives in such unpredictable environments. It offers strategies to enhance efficiency, profitability, and security. Among its leaders, one stands out for his enduring insights: John Boyd.

"GENGHIS JOHN"

Colonel John Boyd, later known as “Genghis John” for his fiery style, was a fighter pilot during the Korean War, flew F-86 Sabers against the Soviet-made MiG-15. While the MiG-15 outperformed the F-86 in power and agility, the F-86 excelled in stability and high-speed targeting. These advantages allowed Boyd to develop groundbreaking combat theories based on agility and precision.

After the war, Boyd trained pilots at the U.S. Air Force Weapons School. He also spearheaded the Lightweight Fighter Program, which led to the F-16 Falcon and F-18 Hornet. These aircraft remain essential for militaries worldwide.

Later, Boyd became a consultant for the Pentagon, sharing his theories on strategy beyond warfare. His thinking now shapes approaches to business, sports, and even litigation. Known for his fiery communication style, Boyd earned the nickname “Genghis John.”

OODA

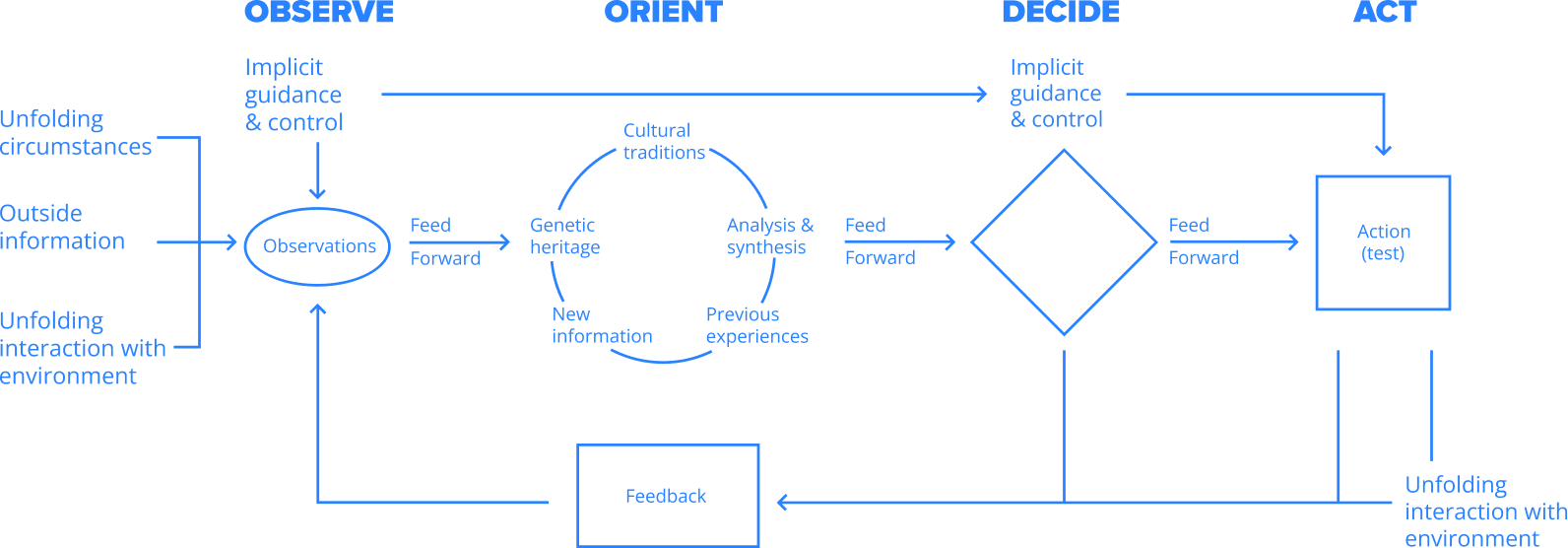

John Boyd also authored the concept of the Observe-Orient-Decide-Act (OODA) loop. It helps organizations thrive in chaos. Its strength lies not in rapid decision-making but in its adaptability. By understanding and exploiting uncertainty, the OODA loop in business fosters agility and initiative.

Here’s "loop" conceptualized by Boyd:

Observe

Gather and analyze information constantly. This includes tracking market trends, monitoring customer behavior, and recognizing external changes. Staying alert helps you make informed decisions and respond effectively to challenges.

Orient

This phase lies at the core of OODA. Analyze data, reflect on past experiences, and synthesize insights to build a clear understanding of your position. Companies must align their people at every level around a shared vision to maximize opportunities and gain a competitive edge. This principle also serves as a foundation for developing a solid DevOps transformation strategy.

Decide and act

When your observations reveal an opportunity, test it. Develop and execute a hypothesis. Successful outcomes should be optimized and scaled. If you fall short, use the insights to refine your approach. This iterative process mirrors the Build-Measure-Learn cycle from Lean Startup methodology, reinforcing the dynamic nature of innovation.

Speed

Timing is crucial. Delays can undermine even the best decisions. Boyd stressed that shared vision and implicit trust enable teams to act quickly without waiting for detailed instructions. Friction shrinks, and execution speeds up when everyone understands the goal.

Staying relevant

Boyd didn’t outline how to implement OODA in a modern organization, but today’s technology aligns perfectly with his ideas. Continuous data streams, predictive analytics, and AI support observation and orientation. Automation and cloud systems streamline action. Despite these tools, many businesses fail to harness their full potential.

Legacy IT systems, siloed data, and outdated processes stifle progress. Without organizational alignment and seamless communication, insights stay trapped, and innovation stalls. To thrive, you need robust solutions and agile practices that break down barriers.

HIGH PERFORMING IT ORGANIZATION

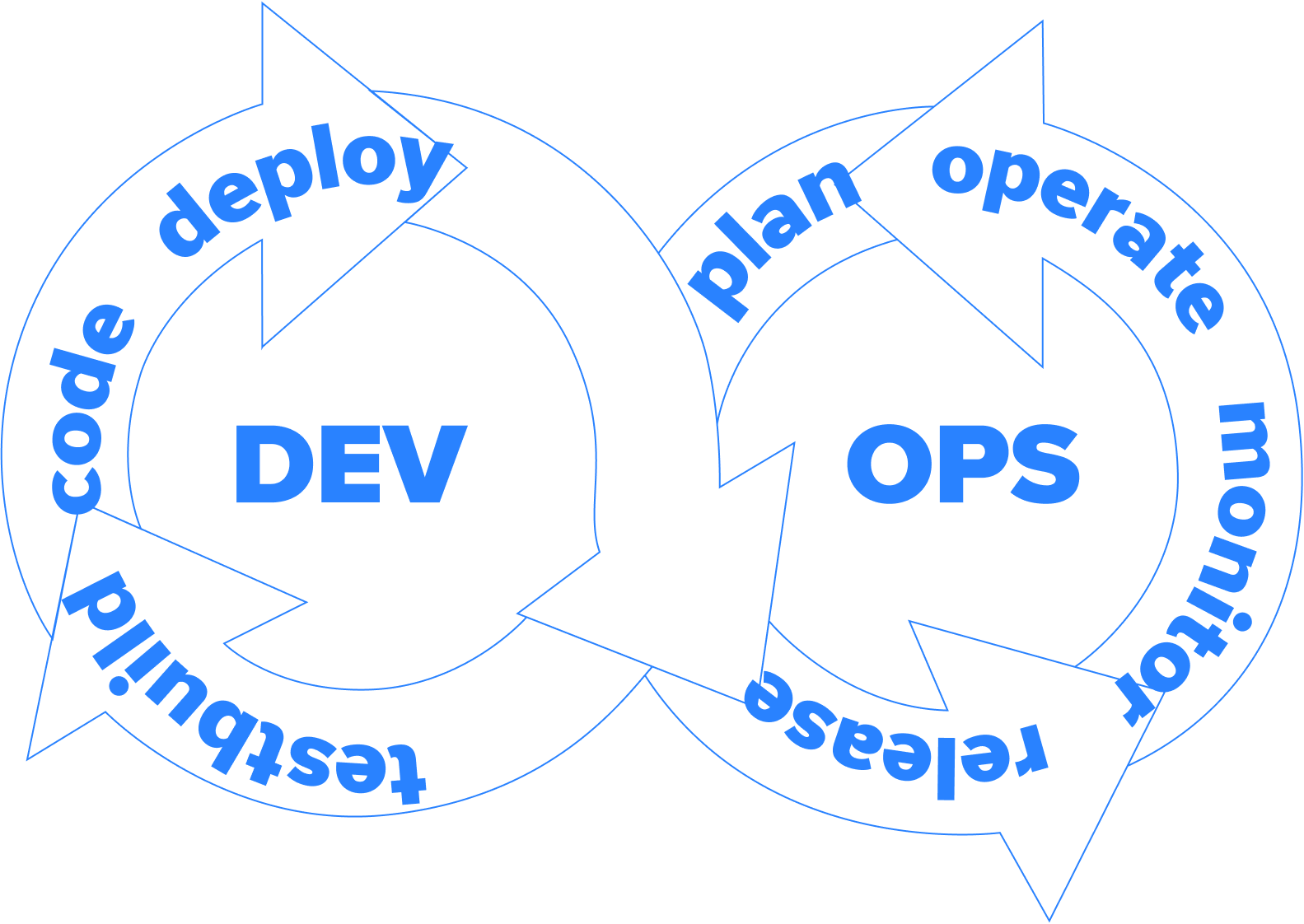

The DevOps movement embodies Boyd’s principles. Born from a 2009 Flickr presentation about integrating development and operations, DevOps unites people, processes, and technology to deliver faster, better outcomes.

Culture and collaboration

DevOps eliminates silos between IT departments — primarily development, operations, and IT project management. This fosters a culture of trust, experimentation, and collaboration among individuals. This concept aligns closely with Boyd's principles of Fingerspitzengefühl understanding and Einheit. A strong devops strategy builds this trust further and enhances alignment.

Continuous delivery

Through DevOps, businesses improve efficiency by rethinking processes. Smaller, incremental changes minimize risk while delivering value consistently. Automated testing and reduced manual labor lower the chance of human error, aligning with Boyd’s concepts of Schwerpunkt and Auftragstaktik. Using a continuous delivery framework, organizations enhance their ability to respond and adapt swiftly.

Technology and automation

DevOps leans on automation to reduce repetitive work. Tools for infrastructure, deployment, and testing accelerate progress and free up talent for higher-value activities. These automation practices reinforce Boyd’s principles of speed and implicit guidance.

WHY DEVOPS MATTERS

DevOps adoption continues to grow. Without it, companies struggle to meet customer demands, falling behind agile competitors. Manual deployment fails often, especially under pressure. Lack of DevOps also slows improvement and makes responding to market changes harder.

Boyd’s OODA loop teaches that adaptation never ends. Staying relevant demands constant reorientation and optimization. At SoftServe, we understand digital transformation as a continuous commitment. It’s a process, not a destination.

Think big. Start small. Speak with SoftServe’s DevOps experts and transform your approach today.

Start a conversation with us